Coming into yesterday’s slate of MLB games, there had been about 39,000 plate appearances across the league. Subtract the strikeouts (9500), walks (3500) and batters hit by a pitch (500) and that leaves about 25,500 balls put into play. About 8100 of them fell in for hits, 1200 were home runs.

MLB classifies all those batted balls as ground balls, fly balls or line drives. Within the category of fly balls are ones that are played by infielders. The common name for those kind of hits is pop-up. MLB uses the abbreviation IFFB (infield fly ball) in their stat tables. As you would expect, the batting average on pop-ups is low (.021 in 2021). For you saber dorks, the xBA on a pop-up is .035.

Baseball has been collecting data on batted balls since 2002. Since then, baseball’s pop-up rate has been steady, at 10-11% of balls put in play. The pop-up rate in the 2021 season is 10.4%. Again, that means 10.4% of all balls put in play are fly balls to infielders.

A lot is made these days about launch angle. The optimal launch angle for home runs is 25º-30º. Batters work like crazy to hit the ball in that range. One way pop-ups reveal themselves in game reports is by launch angle. When you see numbers like 63º or 81º on balls in play, you know it’s a pop-up.

Because of the low hit probability on pop-ups, batters try to avoid hitting them.

For years, Joey Votto was the Reds player mentioned whenever the topic of pop-ups came up. That’s because Votto almost never hit them. In his 2010 MVP season, the Reds first baseman hit exactly zero pop-ups. Well, that was one year a long time ago, you say? Votto also had no pop-ups in 2016, 2018 or last year in 2020. Nada. Zilch. Over eleven years of his career (2010-2020), Votto’s pop-up rate was less than 1%. That’s in a league where the average is 10 times that.

But this little post isn’t about Joey Votto.

The Reds have another pop-up freak on their hands. This one is a pitcher. And I could give you ten guesses and you might not get the name right. Here are a few clues.

This pitcher has faced 25 batters. He’s surrendered no hits and two walks. He has struck out eight batters.

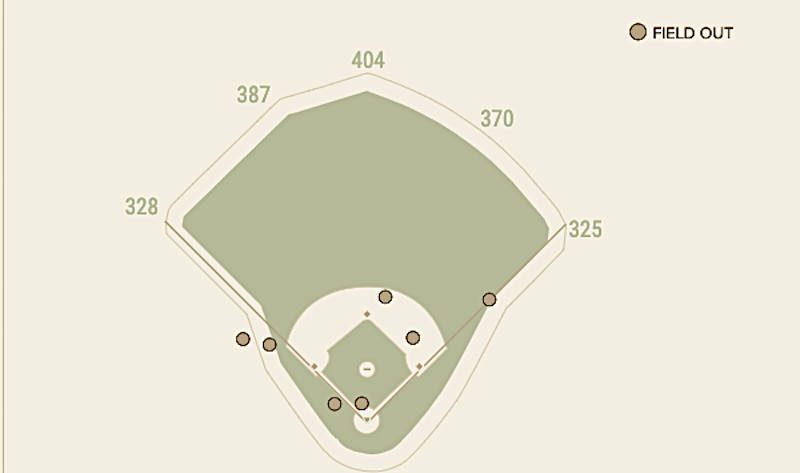

The player is reliever Heath Hembree and he’s given up 15 balls in play in 2021, all of them outs. You’d expect of 15 that one or two of them would be pop-ups. But Hembree has induced eight fly balls to infielders on the 15 balls he’s allowed in play. That’s a pop-up rate of 53.3%. In Hembree’s 10th-inning appearance in Pittsburgh yesterday, the first two batters he faced popped-out to Jonathan India at 2B.

The players on Hembree’s pop-up lists aren’t weak hitters. Try Nolan Arenado:

Or Anthony Rizzo:

Dodger phenom Gavin Lux:

Even former NL MVP Kris Bryant has been a Hembree victim:

That’s half.

A couple days ago, after Hembree had gone 6+ innings (now 7+) without giving up a hit, I started to research him a bit to see what, if anything was going on.

Hembree is a 32-year-old right-handed reliever who has been released by a couple teams. His best years were 2016-2018 with the Boston Red Sox when he had a 4.00 xFIP. The last two seasons, with Boston and the Phillies, Hembree’s xFIP ballooned to 5.73. The Red Sox had traded him to Philadelphia, who chose not to re-sign him after 2020. Hembree got an invite with Cleveland to spring training, but didn’t make the cut there. The Reds picked him up on March 22 and assigned him to their alternative site in Louisville.

With the Reds bullpen going through things, they called for Hembree and Ryan Hendrix on April 23. Hembree pitched for the Reds that day. He performed the obligatory “walk the first batter you face” then got Nolan Arenado to hit that pop-up above.

Since then, it’s been a non-stop pop-up freak show with Henbree.

Is there something behind it? Maybe a magic Spincinnati potion? That’s what I had set out to learn a couple days ago. Instead, I found all these pop-ups. Hembree has thrown just two pitches this year, a fastball (60%) and slider (40%). They are equal-opportunity IFFB-deployers. In those videos, Arenado and Rizzo popped-up sliders. Lux and Bryant went down on fastballs.

I checked pitch velocity. Hembree’s fastball is right at career levels. His slider down by a couple mph. Maybe he’s getting more spin with this pitching staff and that’s causing Hembree’s fastballs to ride more? Nope. His fastball spin-rate hasn’t changed. His slider spin-rate is increasing, but that should in theory cause the pitch to drop faster than before, inducing ground balls, not short fly balls.

Pitch movement? Again, nothing helpful. Neither his vertical or horizontal fastball movement has budged from career levels. His slider has had a couple more inches of vertical break, likely because of the lower velocity and more spin. But again, that works against, not in favor of, pop-ups. Hembree’s slider does have a lot more horizontal break than before. But that’s side-to-side and not something that should get batters to swing under it.

So when you look under the hood, there’s no cool explanation for Heath Hembree’s outbreak of pop-ups. At least none that I could find.

As much as you’d like to discover a narrative here, it’s probably random variance at work. Hembree hasn’t become a shut-down guy all of a sudden. He’s just had a good stretch. This silly post is about eight infield fly balls. Get back to me when that number is 40.

You just never know with journeyman relievers. Given the circumstances surrounding Hembree’s acquisition and initial assignment to Louisville, his start is as much a surprise to the Reds as anyone. In early April, he was this year’s Burke Badenhop, Ross Ohlendorf, Kevin Gregg, Pedro Strop or Steve Delabar. Heck, this year’s Sean Doolittle, Cam Bedrosian, Carson Fulmer, Art Warren or Noé Ramirez.

On the optimistic side, you can get a good month or year out of players like Heath Hembree before gravity sets in. Think Jared Hughes or David Hernandez as recent examples. That’s the best teams who shop in these markets can hope for. We should enjoy every towering infield fly ball while we can.