We’ll learn soon if the Reds will take the field against the Chicago Cubs on Opening Day as planned. MLB informed the players last week they view February 28 as the date when spring training would have to start to keep the regular season on track.

That deadline is a week from tomorrow. It would allow a four-week window of preseason preparation. That seems about right given what was learned in the on-again, off-again start to the 2020 season.

Teams would have to cram most of the normal offseason roster construction – arbitration hearings, free agent signings, trades and curb shopping the leftovers – into that compressed time. That’s in addition to getting players into shape for professional baseball games.

Player acquisitions have been shut down since December 2, when baseball’s owners chose to impose a player lockout. The move followed the expiration of the previous Collective Bargaining Agreement the day before and represented the sport’s first work stoppage of any kind since the 1994 player strike.

So, it’s fair to say the labor dispute will reach a critical inflection point this week.

Beyond the logic of calendars and impending deadlines, it has been reported that owners and players have gathered in Florida the past few days. That’s where the negotiations are expected to intensify this week with multiple bargaining sessions.

The Crux of It

The overarching economic issue is this: Players are the source of value to the sport – the product – but their salaries have been flat or declining for several years at a time when baseball and related revenues are soaring, in lockstep with team values.

The players want to reverse that adverse trend. The owners want to maintain the status quo labor arrangement that is enriching them, while adding lucrative postseason games. Both sides are powerful and locked in.

Money to Young Players

The union’s primary strategy to boost salaries is to focus on younger players. In 2019, 54% of playing time went to players with less than three years of service time, but only 10% of pay did. The union is pressing three ways to accomplish this:

- Increased minimum salaries

- An owner pool of bonus money for pre-arbitration players

- Reduced major league service time before players earn the right to arbitration.

Where do each of these stand?

Minimum Salaries Under the previous CBA, minimum salaries had increased from $535,000 in 2017 to $570,500 in 2021. This month, owners proposed step increases for minimums of $615,000, $650,000 and $725,000 over a player’s first three years with a major league team. The MLBPA has proposed the minimum would increase from $775,000 in 2022 to $875,000 by 2026.

Pre-Arb Bonus Pool Owners have agreed in principle to creating an extra pool of money for pre-arbitration players. But they’ve offered only $15 million for it, spread over 30 players. The union has proposed $115 million, spread over 150 players. Under both side’s proposals, this pool would be merit-based.

Note: 150 players is an average of 5 per team. $115 million would average less than $4 million per team.

Service Time to Arbitration Previous CBAs have established three years of service time as the standard wait for a player to earn the right to arbitrate his salary. The point of contention in the labor talks is over the group of players who have at least two years of service time but not yet three years.

The CBA that just expired allowed for 22% of the players in that category – the 22% with the most service time — to qualify for arbitration. They’re referred to as Super Two players. Nick Senzel, with two years plus 150 days, is the one Reds player in the 2+ group who falls into the top 22%.

In the current negotiation, the union had asked that 100% of those players qualify for arbitration. But they reduced the ask to 80% in last week’s proposal. Owners have been unwilling to budge from the 22% established in the previous CBA.

Competitive Balance Tax

Another contentious issue concerns the league’s Competitive Balance Tax that sets a soft cap on how much teams can spend on payroll. Teams that exceed the set amount pay a “luxury” tax penalty.

In 2021, the threshold was $210 million with tax rates of 20% for first-time offenders, 30% for teams that exceeded the limit in consecutive seasons and 50% if it had been three or more consecutive years. Higher tax rates applied at the $230 million and $250 million levels. Only the Padres (by a little) and the Dodgers (by a lot) exceeded the target last year. A few other teams seemed to be staying just below it.

Owners want lower payroll spending. They have proposed a low and slow increase in the CBT threshold from $214 million to $222 million in 2026. Second and third tiers would be $20 million and $40 million above the first tier. They also want tax rates to increase substantially and offending teams forfeiting draft picks.

The players, who don’t really want any CBT, are trying to get levels as high as possible. They’ve proposed the threshold start at $245 million and increase to $273 million in 2026 and keep tax rates the same.

DH, Postseason, Draft Lottery, Etc.

The sides have agreed to a universal DH and the abolition of compensation penalties for teams that sign free agents. The owners want advertising on uniforms. The players have agreed to that contingent on the rest of the CBA being completed.

The owners proposed an increase in postseason teams from 10 to 14. The players have agreed to 12, contingent on the rest of the CBA being completed and with consideration of a realignment to two divisions per league.

To combat tanking, both sides have agreed to a draft lottery for a certain number of top picks. The owners have proposed a lottery for the top three selections, while the players have proposed one for the top eight.

Each side have advanced ideas regarding service time manipulation. The players have proposed a system where the best rookie players would earn extra service time. The owners have proposed giving draft pick incentives to organizations that promote Top 100 prospect players earlier. They could agree to adopt both.

How Much Money are we Talking About?

As you can see, the issues being negotiated don’t involve fundamental ideological change, the type that can create complete intransigence in negotiating. In total, the union ask has been small-bore, tweaking the current structure.

Boosting minimum salaries and the pre-arb pool to what the players are proposing would provide $180 million in salary to younger players. One estimate puts the total new spending on players – IF owners gave the union everything it has asked for – at $440 million dollars. In an $11 billion industry, that’s 4%.

Everyone knows neither side will get everything it wants. Bottom line, what’s at stake in these negotiations is akin to whether the players get 43% of the revenue or 44%.

That 1% swing amounts to about $110 million, or less than $4 million per team. That’s in the context of owners also benefiting from new postseason revenue and advertising on uniforms.

Heading Toward Impasse?

The National Labor Relations Act governs labor talks, enforcing a duty of the employer and union to bargain in good faith over wages, hours and working conditions. But it doesn’t require the two sides to reach agreement. Federal law limits the government’s substantive role so workers and management can determine for themselves how they relate.

So, what happens if the two sides reach a stand-off in negotiations?

The employer can declare an “impasse” (that’s a labor law term of art) subject to approval by the NLRB and reviewed by courts.

If an impasse is granted, the employer can impose it’s “last, best, final offer” on employees, as long as those terms were offered to the union before the impasse was declared. In the present case, owners could offer the highest minimum salary structure they had presented during negotiations. Then, individual major league players would have to decide to cross the picket line and accept those offers. Minor league or other replacement players could as well if teams allow it.

Are we headed toward stalemate and the declaration of impasse this time?

It’s possible that’s where baseball owners are angling to end up, though most experts feel the situation does not yet meet the criteria. If impasse were declared, the players would certainly file an unfair labor practice charge with the NLRB like in 1995. No matter who won at the NLRB, the baseball schedule would be set way back and acrimony dialed way up.

The Owners Lockout

The owners could lift their lockout any time they want. Spring training and the regular season would proceed as normal with the sides negotiating while using the past CBA as a default guideline.

Why won’t the owners do that?

Initially, MLB said it imposed a lockout to “jump-start” the negotiations. That rationale didn’t pass the laugh test since owners then waited 43 days to make their next offer.

So, what is behind the owners’ all-out commitment to lockout?

Owners say the lockout pre-empts a union strike later in the season, when the players have more financial leverage. In 1994, players went on strike in August. The timing helped the players, who had received most of their pay for the season. They were able to threaten the postseason, which is extremely lucrative for the owners because of broadcasting rights.

Owners say they want to prevent that scenario playing out again. But given the relatively small amount of money at stake and the non-fundamental (not strike-worthy) nature of the disputed issues, is the threat of getting to a mid-summer strike that high? Neither side would really want to stop games. They could simply reach an agreement in the months leading up to that point.

A Fan’s Lament

Unfortunately, negotiations have not progressed much since our last newsletter. The owners and union have expressed resolve, flexing their considerable strengths. Players come armed with unity, a strike fund and unique skill set. The MLBPA is known as the most powerful union among the professional sports.

On the other side, the owners are men used to not being told “no.” They are insulated from accountability by private ownership. Their billions in wealth prevent them from feeling the economic fallout of a prolonged dispute. Some are extreme anti-labor ideologues with aim set squarely on busting or weakening the union. It only takes eight hardline owners to derail any agreement.

Commissioner Rob Manfred recently said it would be a “disastrous outcome” for the sport if any regular season games were missed.

Looking objectively at the issues – the small differences and easy compromises – the February 28 deadline could focus attention and precipitate timely resolution.

We have to hope reason will prevail.

Sadly, we’ve seen precious little cause for optimism. The owners ought to be the game’s stewards with the public’s interest in mind. Instead of lifting the lockout, which they could do tomorrow, they seem determined to squeeze every nickel and dime of wealth they can from the national pastime.

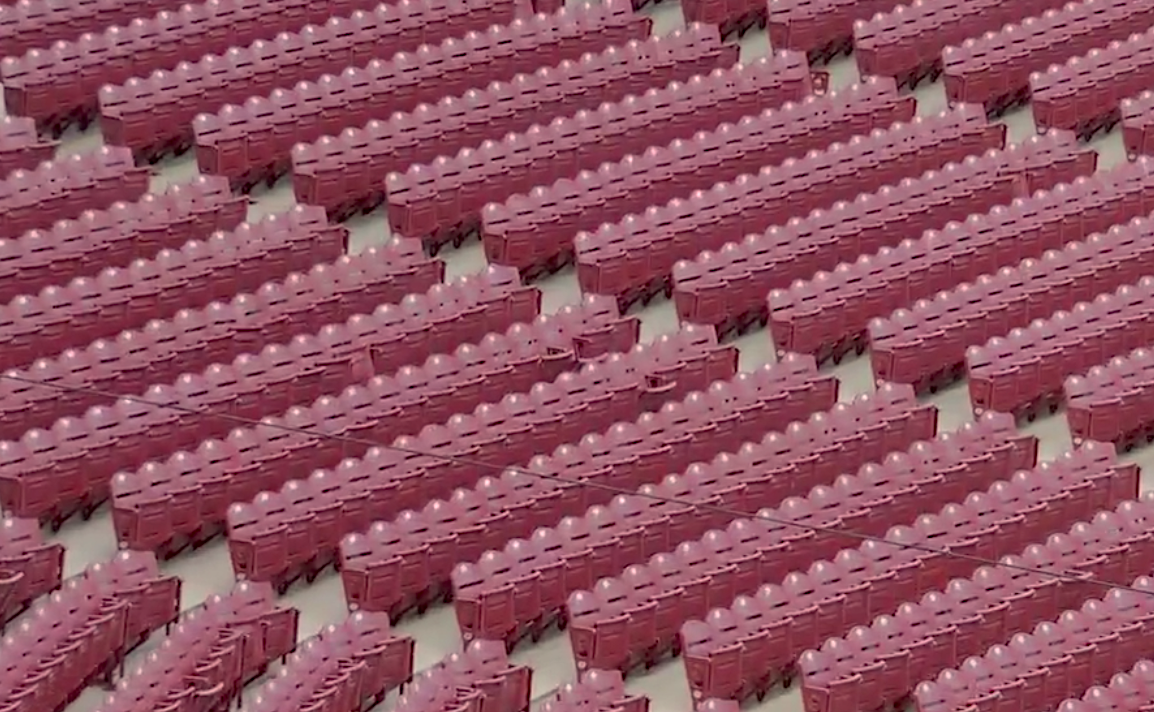

Fans were missing from baseball throughout 2020 and the early part of 2021. We’re staring down a third spring training and possibly more removed from the game. This time, it isn’t a virus that’s causing ballparks to fall silent. It’s the unbridled selfishness of the owners.

We fans have created billions of dollars of wealth for these men, these families, these owners. Yet it’s not just the players who are locked out. We are, too.

This is a complicated negotiation, because the owners have factions within their ranks, as do the players. The Yankees don’t see things the way the Royals do, and T.J. Friedl has interests that differ from those of Nick Castellanos.This has the effect of making the negotiations slow, because each side then has to take the other side’s offer, work up a consensus, and then head back to the table. And each side has low-balled the other, just to feel them out; as usual with sophisticated negotiators, low-balling didn’t accomplish much.

One very good sign from the last session is that each side’s main negotiator met one-on-one for 20 minutes after the larger meeting. Those are the sessions where the lead guys can talk turkey and actually start setting up how they are going to breach the gap between them.

I don’t believe that they are nearly as far apart as the public narrative suggests. $4 million a team is not worth bloodshed. So, I don’t think any team or group of players really wants to lose any regular season games. (Not even the Pirates.)

Reasonable revenue sharing is a good thing for the players, and the CBT is part of that, so I think they will find a middle ground. The players need a financial structure that gives all 30 teams — if they manage themselves well — a realistic shot at contenting for a title on at least a semi-regular basis. Players will make more over the long run with 30 viable

employers, as opposed to 8. Baseball’s inherent weakness is that the Yankees and Dodgers, etc., will generally compete almost every year, whereas the Reds, Royals, etc. have to be both very lucky and very good to compete even half the time. (The Rays are doing it with elite player development and brutal efficiency at never giving out long-term contracts to older players.)

A properly balanced revenue-sharing system –which both sides need — would (1) give the Reds a fair chance to compete, (2) incentivize for the Yankees/Dodgers to maximize their own local revenue while still sharing the wealth; and (3) punish teams that accept shared revenues without some reasonable plan to compete in at least the mid-term.

Splitting up $10.5 billion/year is not easy, nor should anybody expect it to be easy.

I agree with all of this. A salary floor for each team, aided with more revenue sharing, could be set to boost overall spending on payroll even with a soft cap at the top that the owners like. Nothing would do more to get to the point where all 30 teams would have a realistic shot as you say. I don’t know why the players seem so much more fixated on payroll ceiling than floor.