Back in 2021, we took a look at how the Reds’ catchers were impacting the performance of pitchers, both on an individual pitcher level and with the team as a whole. In that article, the focus was on comparing Tucker Barnhart to Curt Casali. Fast forward two years later and Casali is back with the Reds and once again making a positive impact on Reds pitchers.

To set a background, let’s first talk about how a catcher can impact the game behind the plate. Naturally, stopping the run game is part of that, and years ago was the primary factor fans would consider. In today’s game, a lot of the focus has been shifted toward blocking and framing, though that still doesn’t tell the full story. It’s much tougher to quantify, but catchers also have impact via game calling, and just building a good relationship with the pitching staff in general.

In the 2021 article, we looked at data from 2018-2020, and generally concluded that Reds pitchers as a whole tended to have a lower ERA and FIP with Casali behind the plate as opposed to Barnhart, while striking out more and walking fewer hitters. A similar trend showed up for Luis Castillo and Anthony DeSclafani, always seeming to perform better with Casali behind the plate, while both Tyler Mahle and Sonny Gray saw mixed results across their sample sizes with the two catchers.

Before diving into that data for current Reds pitchers and catchers, let’s start by looking at the more traditional defensive metrics – framing, blocking, and throwing.

Luke Maile has generally been a slightly below average framer, posting negative framing runs in four seasons, posting exactly zero twice, and posting four framing runs in 2018. Prior to 2023, he had been a very good blocker, with four blocks above average in 2018, 2019, and 2022, with one block above average in a much smaller 2021 sample. He’s been a perfectly average thrower in each of his last four seasons, including so far in 2023.

Casali has been a bit of a mixed bag when it comes to these three aspects of his game. He posted -2 framing runs in 2018, -1 in 2019, 1 in 2021 and 2022, and -2 last year. He posted two blocks above average last year, but -5 in 2021 and -6 in 2020. He was below average throwing out runners in 2021 and 2022.

Tyler Stephenson has been below average with blocking and framing throughout his career. His framing has actually gotten worse in every season so far, though his blocking improved from -4 blocks above average in 2021 to -1 last year, and zero this year. He’s been about average as a thrower.

On the surface, it seems that both Maile and Casali have been much better defenders than Stephenson, as we would expect. While the 2023 data slightly favors Casali, there isn’t a true standout among the two over a larger sample size in recent years. Still, this is only looking at a small part of the picture. Now, we can attempt to quantify the impact of the three catchers from a game calling perspective.

Much like in the 2021 article, let’s start by looking at the performance of the pitching staff as a whole with each of the three catchers behind the plate. As a reminder, FIP (fielding independent pitching) splits by catcher aren’t available on any website, but we can calculate this for individual seasons using this formula from Fangraphs.

Of course, there are many factors that could influence this that are outside of the catcher’s control. Given the still relatively small sample size, a single blowup game could skew the numbers fairly easily. One example of this can be seen by removing the June 7 game in which the Reds gave up 10 runs from Casali’s numbers. This drops his innings caught to 181, while dropping his ERA to 3.78 and his FIP to 4.10. Additionally, the exact pitchers caught have an impact. For example, Maile has caught 9 of Luke Weaver’s 10 starts, and Weaver has struggled for much of the season.

We can attempt to get an idea of the impact a catcher has on certain specific pitchers as well. To do this, we will look at Graham Ashcraft, Hunter Greene, and Nick Lodolo over each of the past two seasons. Those three pitchers were chosen for a few reasons, including the fact that they’re arguably the most important of the Reds’ starters going forward, and each has a somewhat large sample to go off of. For the purposes of this analysis, we will also include games from last season caught by catchers not currently on the roster, lumped into an “other” group. As always, some caution must be taken regarding the sample sizes.

Hunter Greene

It’s clear in the current sample size that Greene has struggled mightily with Stephenson behind the plate. While his strikeout rate with Stephenson catching is a tick better than when he’s caught by the others no longer on the roster, and his walk rate is better with Stephenson than any other catcher besides Maile, his ERA and FIP are both significantly higher with Stephenson. Part of this can be chalked up to home runs, as he’s allowed 17 with Stephenson behind the plate compared to just 15 with anyone else, in nearly double the amount of innings. It’s possible that at least part of that can be attributed to ballpark or opponent factors, but it’s still at least a bit concerning. Two of Greene’s three career games allowing more than two home runs came with Stephenson behind the plate.

The sample sizes with Maile and Casali are still rather small, and difficult to draw conclusions from at this point. The key takeaway with Greene is the struggles with Stephenson, and it will be interesting if the Reds continue to avoid this pairing, as they have done in each of Greene’s past four starts.

Nick Lodolo

In Lodolo’s case, the vast majority of the innings lumped under “others” belong to a single catcher – Austin Romine. The two had a very good working relationship in 2022, and this further supports the hypothesis that catchers can have a significant impact on a pitcher’s performance. Sample sizes with Casali and Stephenson are still small, but the numbers with Stephenson behind the plate are eye-popping. These numbers encompass six starts for Lodolo, in which opponents have posted an OPS over 1.100 while striking out less and walking more than they have when another catcher is behind the plate for Lodolo. Once again, a concerning trend given that the expected “catcher of the future” and a key piece of the future rotation have not had any success as a pairing.

Graham Ashcraft

Ashcraft’s trend is quite different than Greene and Lodolo. In Ashcraft’s case, his best performance on the mound by ERA, FIP, and strikeout rate has come with Stephenson behind the dish. While he’s walked hitters at a slightly higher rate with Stephenson behind the plate, it hasn’t seemed to cause any significant issues. It’s worth pointing out that Ashcraft’s numbers across the board leave a lot to be desired, so he will be looking to improve with whoever is behind the plate going forward.

Conclusion

Given all this data, what conclusions can be drawn? It still seems reasonable to hypothesize that the catcher does in fact have some impact on a pitcher’s success, or lack thereof. Stephenson’s defensive metrics combined with the performance of pitchers when he is behind the plate paint a concerning picture and cast at least a bit of doubt if he truly can be the Reds’ catcher of the future. While a bat-first catcher is not unprecedented, and could potentially work in the right scenario, Stephenson’s bat will need to return to closer to the 134 wRC+ he posted in 2022 if the Reds want it to be a truly viable option.

At the very least, the data shows that the Reds benefit from having some sort of defensive-minded veteran presence behind the plate to pair with Stephenson. While there isn’t a slam-dunk answer to whether Casali or Maile is the better player overall, the conclusions we can draw on game calling at least lean in the direction of Casali. His reputation backs that up, as there have been articles praising Casali for his work with pitching staffs in the past, even beyond just his time with the Reds. If the end of the Reds’ three catcher experiment is near, it will be interesting to see which route they ultimately opt to go with Casali or Maile. Regardless of which they choose, it would be in their benefit to continue pairing one of Casali or Maile with the younger pitchers, to help them continue to improve and become more confident at the Major League level.

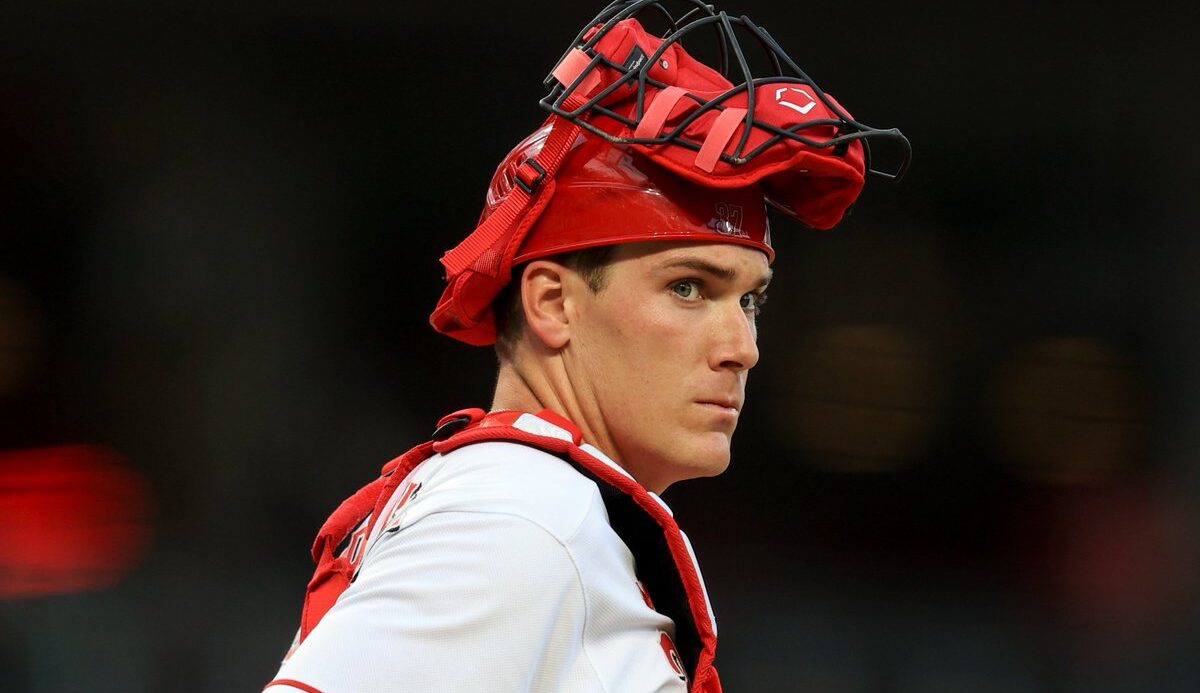

Featured Image: Twitter

Kyle, thanks for a really interesting article. I absolutely believe that a catcher has a significant influence on the pitcher’s performance, and most of it is very difficult to analytically quantify. Overall, I think the eye test and other commentary from players tells us more than most data. The sample sizes are too small and the noise too great to make me comfortable reaching a conclusion from the data.

For example, Tyler caught a lot early last season when Lodolo and Green were making their first starts in the majors, then was hurt the second half of the season when they each improved significantly. Hunter Greene gave up a lot fewer homers in the latter part of the season, and I doubt that improvement was due to Tyler not catching him. His pitching improved, and any catcher who didn’t catch him in the first couple months, but then caught him during those final weeks of the season is going to look better on the spreadsheet. Ashcraft didn’t have the growth and improvement curve that Greene (and Lodolo) had, so the catchers who caught him later in the season didn’t look better than Tyler.

I can imagine a statistical model that would get closer to meaningful conclusions about catcher influence on each pitcher, but it’s complicated and probably beyond what we can model from Fangraphs. (Analysis of how each opposing hitter fared compared to their norm, adjusting for each time through the order, each time facing a pitcher in a season, and more.)

Thanks for the article!

(I’ll also post this to the thread.)