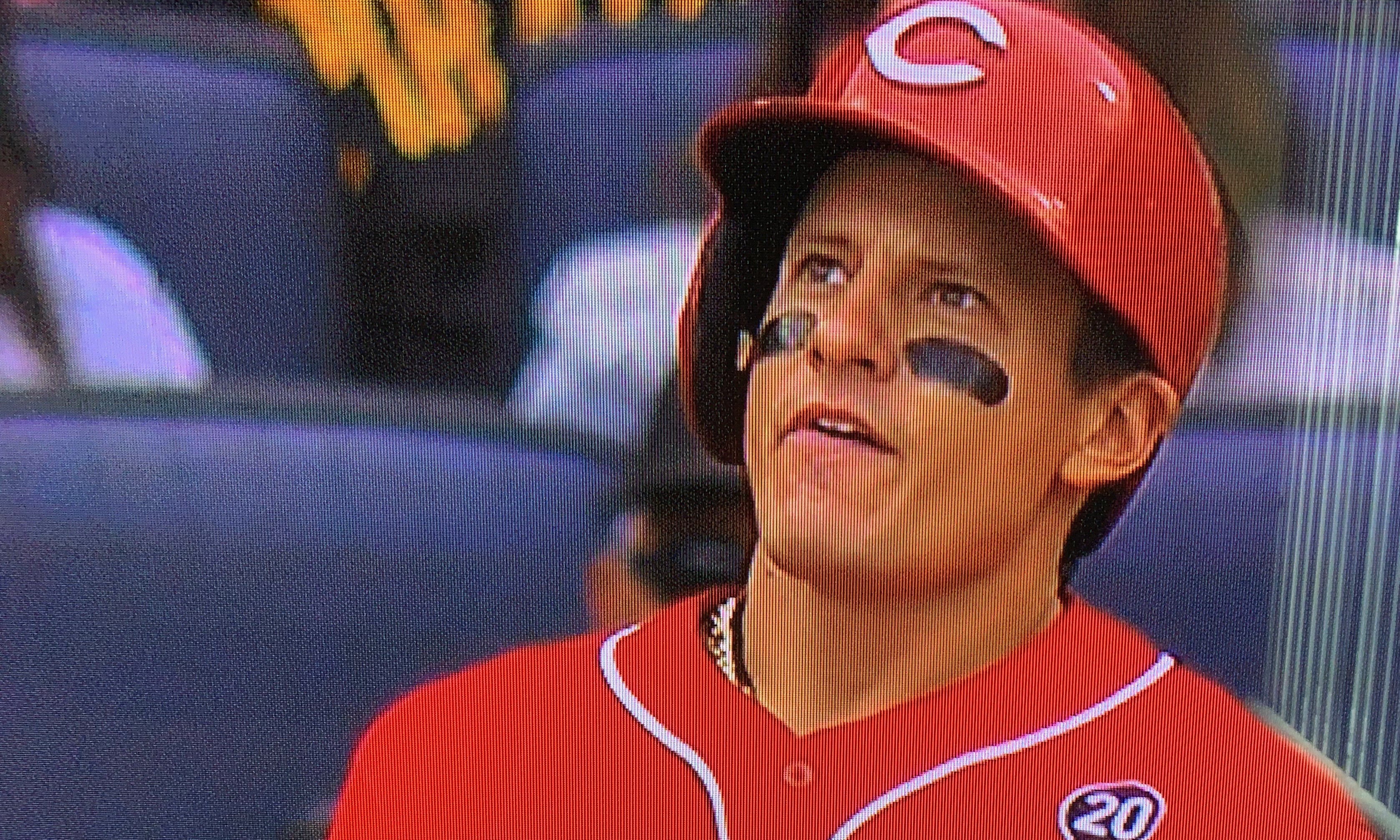

On May 28, Derek Dietrich entered into Scooter Gennett status as a folk hero in Cincinnati Reds lore. The beekeeper/electrician was already well on his way, but he cemented it that night. Not only did he smack three home runs against the Pirates, but the game also served as revenge against Clint Hurdle and the team that intentionally tried to bean him earlier in the season for admiring his work for too long.

After that contest, an 11-6 win for the Reds, Dietrich was hitting .254/.364/.720 with 17 home runs and a 166 wRC+. For reference, Mike Trout has a career 173 wRC+. For the first two months of the season, Dietrich was hitting almost as well as the best player in baseball.

As fun as that was—Dietrich will undoubtedly hold a place in the memory of Reds fans for years to come after his early-season heroics—he wasn’t going to keep up that pace forever. Unfortunately, regression has come.

Saturday’s loss to the Indians was Dietrich’s worst game of the season. He didn’t just go hitless in four plate appearances; he struck out in each one. Although it was just one game out of 162, it was a symbol of his struggles since the night he took ownership of the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Since that game, Dietrich has hit .171/.323/.276 with one home run and a 65 wRC+. Let’s make one thing clear: he’s a better hitter than that. Regressing to the mean doesn’t mean a hitter suddenly turns into a pumpkin. It simply means that a player, especially at age 29, will more than likely decline more toward his career numbers.

Some players defy that. Scooter Gennett is a good example. Many baseball analysts expected him to regress toward his career numbers after his 2017 season with the Reds. He didn’t. But in most cases, a player doesn’t sustain such a huge leap in production.

Dietrich has been an above-average hitter in his career (110 wRC+) despite playing the majority of his games in a pitcher’s park in Miami. But he isn’t Mike Trout. That alone indicated it was worth pumping the brakes before getting too excited about his hot start. Of course, there were other warning signs as well.

First, he was hitting home runs at an unsustainable pace. He set a career high with 16 last year and passed that after 140 plate appearances in 2019. Granted, Great American Ball Park is far more friendly to hitters than Marlins Park. If he continued his pace in terms of homers and plate appearances over the course of the year, he would’ve hit 49 dingers. Dietrich was hitting for more power thanks to two identifiable changes in his approach. He was pulling the ball more and hitting more fly balls.

Many hitters have used this approach in recent years to hit for more power: Francisco Lindor, Jose Ramirez, Matt Carpenter, and Mookie Betts are just a few examples.

But Dietrich simply wasn’t going to continue hitting home runs on 36% of his fly balls. Dating back to 2002, the first year of batted-ball data, only 14 players have sustained a 30% HR/FB ratio in a season: Ryan Howard, Aaron Judge, Christian Yelich, Jim Thome, Giancarlo Stanton, Jack Cust, Domingo Santana, Manny Ramirez, Sammy Sosa, Nelson Cruz, Travis Hafner, and Joey Gallo. Dietrich doesn’t quite belong in that group.

In most cases, a hitter will regress back to his career norm, barring significant changes. Dietrich has clearly made a significant change in his plate approach, which makes it hard to predict where he’ll end up. But his HR/FB ratio has plummeted over the last month, sitting at 5.0% in his last 94 plate appearances.

Dietrich has also struggled to elevate the ball during his slump. While his pull rate has remained the same, his fly-ball rate is down (52% to 39%) and his ground-ball rate is up (32% to 39%). Given that Dietrich faces an infield shift 56% of the time, this hasn’t boded well.

Pitchers have also adjusted to Dietrich after seeing his heavy pull tendencies at the beginning of the year. Take a look at the heat map to Dietrich leading up to and after the three-homer game:

Dietrich is seeing fewer pitches inside and more down and away, which counteracts his pull approach. Pitchers are also throwing him fewer fastballs and more breaking balls.

This is not only contributed to the increase in ground balls but also to more swings and misses. Since May 29, Dietrich has an 18.0% swinging-strike rate. That’s sixth-worst among 226 players with at least 90 plate appearances during that time.

Here are Dietrich’s career numbers against each type of pitch:

- Fastballs: .363 xwOBA

- Breaking Balls: .248 xwOBA

The league has clearly adjusted to Dietrich, and now he has to counter-adjust. Taking some of those outside pitches to the opposite field may make the opposition more willing to come back inside against Dietrich. Laying off breaking balls out of the zone and until two strikes — easier said than done, to be sure — will force pitchers to throw more fastballs over the plate.

Time isn’t exactly on his side, as Gennett is back from the injured list, likely relegating Dietrich back to a super-sub role in the second half of the season. But if Dietrich can make an adjustment at the plate and produce merely like the hitter he was in Miami, he’ll be one heck of a bench player and still get plenty of starts against right-handed pitchers.